In college, I took a behavioral finance class that examined the logical fallacies humans are naturally susceptible to.

Our professor challenged us with logic tests and brain teasers in an effort to rewire the (sometimes dangerous) natural, surface-level thinking we use in most areas of life.

One of my favorite questions went something like this:

This question is straightforward and seemingly simple, yet many people reach the wrong answer.

The trap response, and the one the majority of students use, is 15 days.

Our brain thinks: half-filled lake = half of the 30 days.

However, the correct answer is actually 29 days.

In fact, if the lake had a total area of 1 square mile (roughly the size of London), on day 15 the patch would only cover about 850 square feet! That’s 1/32,768th, or 0.003%, of a square mile!

Designed by Yale Professor Shane Frederick, the lily pad problem preys on our cognitive bias toward linear thinking by presenting us with an example of exponential growth.

Our brains are ill-equipped to think in exponential terms, which causes us to massively underestimate phenomenon that follow exponential paths, such as patches of lily pads on a lake, or the financial concept of compound interest.

Compound Interest Definition

Considered by Albert Einstein to be the eighth wonder of the world, compound interest occurs when we earn interest on previously accumulated interest.

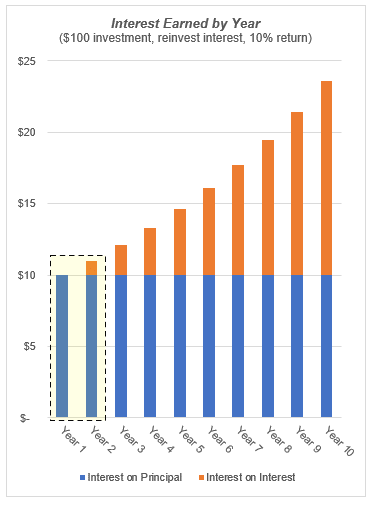

For example, if I invest $100 and earn a 10% return in year 1, I earn $10 in interest (highlighted, right) and my account will grow to $110.

If I leave that $110 invested and earn another 10% in year 2, I earn $11 in interest (highlighted, right) and my account will grow to $121.

In year 2 I earned $11 interest versus only $10 in year 1. How could this be?

That extra dollar is the result of compound interest- in year 2 the account earned 10% on the $10 of interest earned in year 1.

Therefore, in year 2, $11 is earned instead of $10, absent any additional money or effort from the investor.

As seen on the right, this process continues, and by year 9, an investor is earning more on previously accumulated interest than they are on their initial $100 investment.

Snowball Effect – Compound Interest

Warren Buffett likens this process to a snowball rolling down the hill.

As the snowball rolls, it not only grows, but it does so at an increasingly faster rate.

The growth is almost imperceptible at first, but before long, what starts as a fistful of snow quickly and easily becomes a base for a large snowman.

The same thing applies to our investments.

Let’s look at another example.

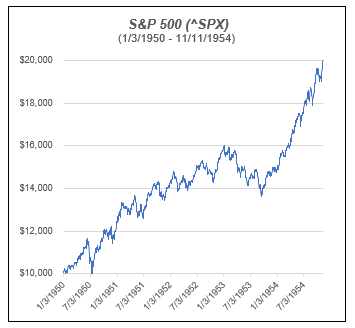

Imagine you or one of your relatives invested $10,000 in the S&P 500 at the start of 1950.

It took 1,216 trading days to earn $10,000 in interest on that initial $10,000 investment (see left).

Essentially, your account took just under 5 years to double in value.

Doubling an investment is great, but earning $10,000 over 5 years is unlikely to make a large impact on the long-term wealth of most people.

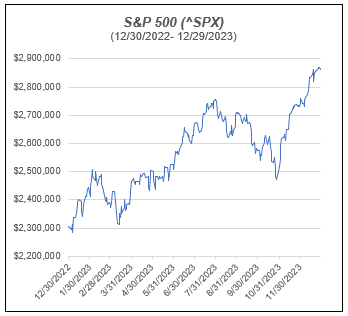

Now let’s say you simply kept that money invested until the end of 2023.

Never adding another dollar AND ignoring dividends, you would have earned over $558,000 in interest… in 2023 alone.

That’s more than 55x your initial investment in a single year.

Instead of taking 5 years to earn $10,000 (as it did above), your investment earned more than $10,000 per week, on average, in 2023 (see right).

Overall, the total portfolio would have grown to over $2,860,000… all from a single $10,000 investment!

Earning Compound Interest Starts with Saving

As seen above, growth in investing happens a lot like Mike Campbell’s bankruptcy in The Sun Also Rises: “Gradually, then suddenly.”

A strong commitment to saving and adding to your portfolio in those slow growth “gradually” years are needed to get the “suddenly” punch in the later years.

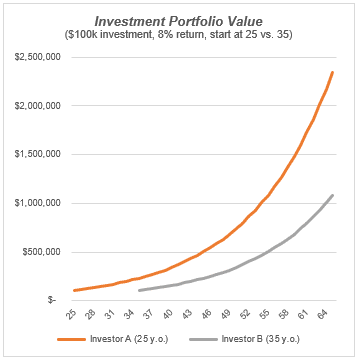

Imagine two investors who each start with the same sum of money and each earn 8% per year.

However, one investor (Investor A) starts investing at age 25, and the other (Investor B) waits until age 35.

By age 65, Investor A will have more than twice as much money as Investor B.

If each investor started with $100,000, 10 extra years of waiting costs Investor B more than $1.2 million.

If Investor B wanted to catch up by adding annual contributions to their portfolio, they would need to add more than $10,000 per year for 30 straight years.

An extra $300,000 in savings is needed just to catch up.

Giving the compound interest machine the dollars it needs to work with can be tough, but as the late investing legend Charlie Munger so tenderly explained, when it comes to saving, “The first $100,000 is a bitch, but you have to do it.”

It Just Takes Time

In Psychology of Money, Morgan Housel posits that Warren Buffett’s “skill is investing, but his secret is time.”

Housel goes on to point out that almost the entirety of Buffett’s fortune was accumulated in the back half of his life.

According to Forbes, Warren Buffett’s net worth was $132.2 billion as of mid-February 2024.

More than 99%(!) of this was earned AFTER his 50th birthday.

At the end of the day, when looking to maximize the power of compound interest, it always comes back to time.

Investing as much as you can, as early as you can, and being as patient as you can, will give you the best chance of long-term success.

Invest early, invest often, and let the wonder of compound interest fill your lake (account) full of green lily pads (dollars).